Once upon a time, quarterbacks were expected to be statues in the pocket. As the team’s signal-caller, your job was to simply pass the ball and execute a game plan. If you weren’t a pocket passer, there probably was a lot of momentum for you to move to a different position.

This was a much simpler time of football analysis, but now, the game has evolved. With offensive play-callers becoming more creative in terms of putting their players in a position to succeed, it appears that, by the eye test, that quarterbacks have different responsibilities than they once did. With quarterbacks like Patrick Mahomes, Deshaun Watson, Josh Allen, and Lamar Jackson taking the league by storm, mobility may be becoming a necessity at the position, rather than a luxury.

Is there something to this? Should all teams be targeting athletic quarterbacks. If so, how should they be utilized, and what is the future of the quarterback position in general? Let us take a closer look!

Mobile Quarterbacks Lead To More Efficient Rushing Attacks

If there is anything we know about modern-day offenses, it is that success is tied to the passing game. Whereas 93.7% of a team’s expected points added per play (EPA/play) can be explained based on their dropback EPA/play, based on the coefficient of determination (r^2), that numbers drops to 41.8% when looking at rushing EPA/play. In other words, passing attacks are more than twice as important when it comes to building a successful offense than one’s rushing offense.

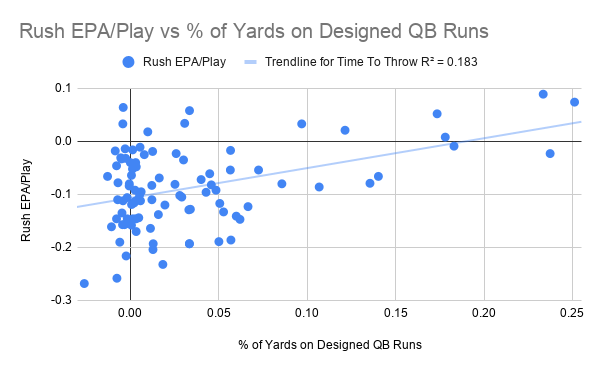

In an ideal world, teams would be passing the ball as much as possible, particularly on early downs. However, even the league’s most aggressive passing teams only pass the ball around 65% on early downs. Thus, it’s still obviously better to have an efficient rushing offense that one that is averaging two yards a carry. That is where mobile quarterbacks come into play:

The greater the amount of a rushing share that comes from designed quarterback runs, the more effective a rushing offense is. Intuitively, this makes sense for a number of reasons. Primarily, if an opposing defense has to be worry about the quarterback AND the running back, it is simply more difficult to maintain responsibility on run fits. The more confusion and chaos you can create for an opposing defense, the better. This may help explain why quarterbacks generally are able to earn more yardage before contact than running backs, and is yet another reason to not invest heavily at the running back position. If rushing attacks are affected mostly by defensive box counts, the only way to combat this, other than simply just passing (which is the best approach), would be to feature the quarterback in the running game.

This season, the top two rushers in terms of yard/attempt were Lamar Jackson and Kyler Murray, who each led rushing attacks that generated positive EPA/play on the ground. Jackson also finished #1 in yards/attempt in 2019, while Deshaun Watson earned that honor in 2018. In fact, there has only been one year in this decade where a quarterback DID NOT finish in the top two in yards/attempt. Want to have an effective rushing offense? Get a quarterback who defenses have to fear.

Quarterback Mobility and Sacks

To measure quarterback mobility, we’ll look the total amount of rushing yards they are able to accumulate. Although this is an imperfect measure, it is the most optimal one, in my opinion: more athletic quarterbacks will run the ball more freqeuntly.

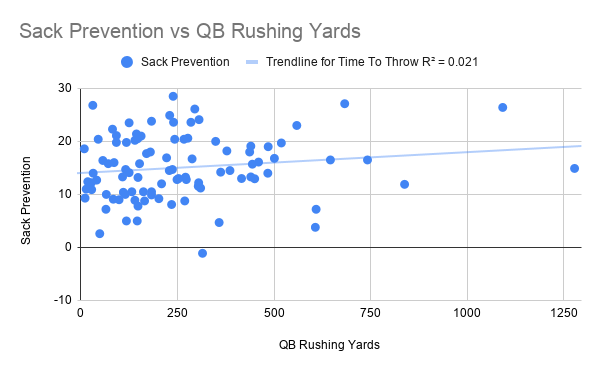

One common complaint of immobile quarterbacks is that they take too many sacks, and place a greater amount of pressure on the offensive line. At least in terms of sack prevention, that isn’t particularly true:

In terms of not converting pressure to sacks, there doesn’t seem to be a great correlation between mobility and sack prevention. This either means that avoiding sacks is an innate trait, or, most likely, that is an unstable metric that varies greatly on a year-to-year basis. In fact, here are the leaders in sack prevention over the past three years:

- Sam Darnold and Joe Flacco 2020

- Josh Allen 2018

- Jared Goff 2019

- Lamar Jackson 2020

- Daniel Jones 2019

- Jacoby Brissett 2019

- Patrick Mahomes 2020

- Drew Brees 2019

- Patrick Mahomes 2018

- Justin Herbert 2020

Here we see some mobile quarterbacks, such as Mahomes, Brissett, Jackson, Allen, and Jones, and then Jared Goff and Drew Brees?? Considering that Kirk Cousins and Matt Ryan are just outside the top ten, I can safely conclude that quarterback mobility does not mean less pressure being converted to sacks. For those curious, Ryan Tannehill/Marcus Mariota in 2019, Derek Carr in 2018, Kyler Murray in 2019, Marcus Mariota in 2018, and Matthew Stafford in 2020 have been the worst at sack prevention. This seems to be a specific trait with Stafford, which is worth keeping an eye on now that he is on the trade block.

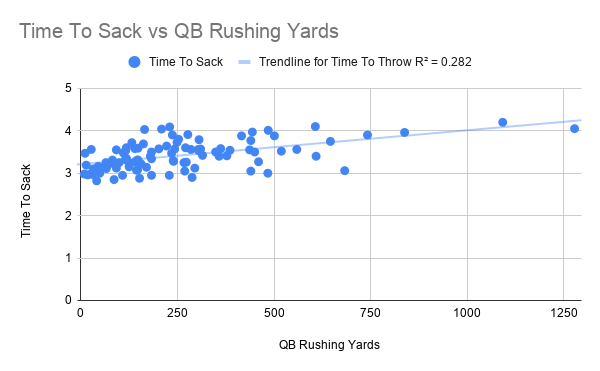

While quarterback mobility does not guarantee better sack prevention, that doesn’t mean that they are just as easy to sack as traditional pocket passers. In fact, dealing with a mobile quarterback is quite the test for pass rushers:

The more mobile your quarterback is, the longer that it will take for them to sack. With sack prevention being rather unstable, I’ll greatly take my chances with a quarterback that is more DIFFICULT to sack. Of the quarterbacks with the longest time to sack, Lamar Jackson, Kyler Murray, and Deshaun Watson appear multiple times, while Jacoby Brissett, Dak Prescott, Josh Allen, Mitch Trubisky, and Patrick Mahomes all rate highly. At the bottom? Pocket passers Drew Brees, Josh Rosen, Eli Manning and Andy Dalton. Interestingly, Ryan Tannehill both does not prevent sacks and is sacked rather quickly, which isn’t an ideal trend.

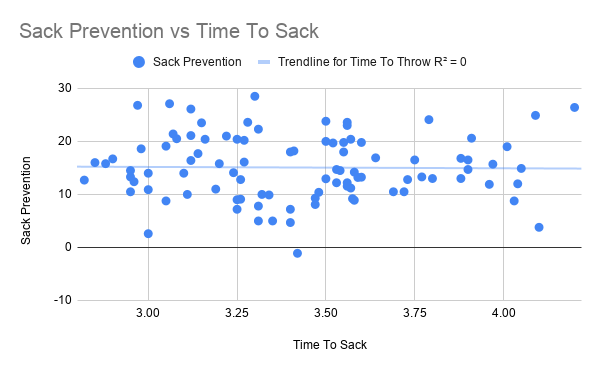

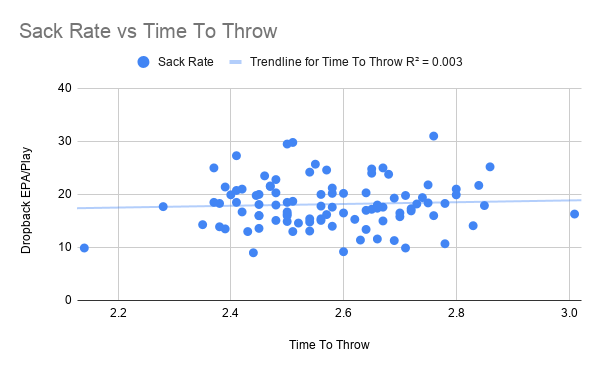

Also, for those wondering, there is zero correlation between time to sack and sack prevention:

So, what does this mean? At the end of the day, preventing sacks is a rather noisy statistic without any great predictive power, so, for the most part, I wouldn’t let it factor much into my evaluation of quarterbacks unless there is a notable trend. However, athletic quarterbacks take longer to sack, which, in theory, makes them more difficult to sack. If you targeting a mobile quarterback, it shouldn’t be that they will prevent sacks, but, rather, that they will simply be harder to bring down.

The Uncomfortable Playing Style of Most Mobile QBs

If you are an old-school head coach or a fan with old-school principles, you may be used to having a quarterback who plays within structure and doesn’t do more than that. In fact, the “game manager” may be your preferred quarterback- they will theoretically be more likely to limit negative plays.

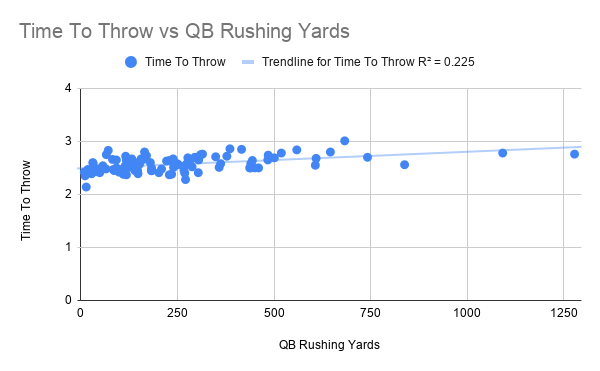

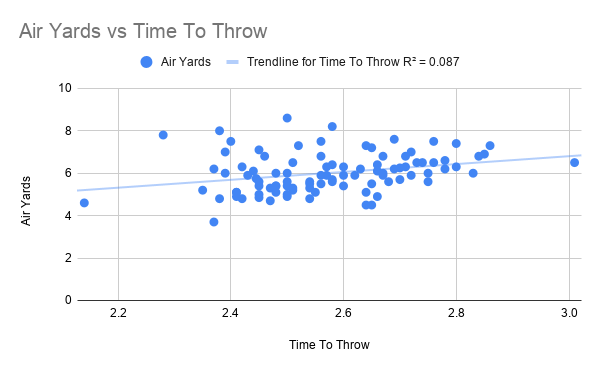

If that is the case, then the new-age of mobile quarterbacks may be uncomfortable at time. For starters, mobile quarterbacks tend to hold onto the ball longer:

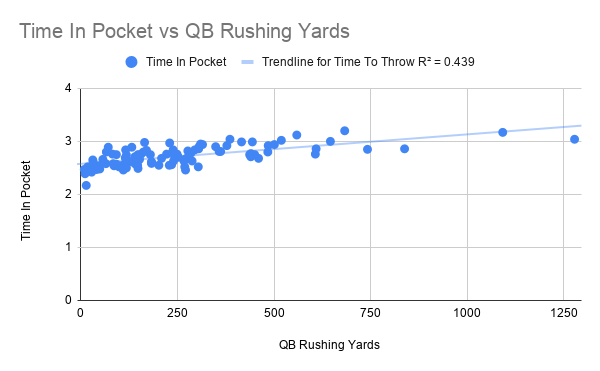

Particularly in the pocket:

Once again, this appears to be a relationship that is mathematically linear and makes sense. The more mobile a quarterback is, the more likely they are to trust their abilities to allude pressure and make “something out of nothing”, which means they will hold onto the ball longer. All it takes is one game of Josh Allen for this to be clear:

However, this is not a reason to lose faith in this new age of quarterbacks. In fact, there is little to suggest that this type of play style is doing more damage at all.

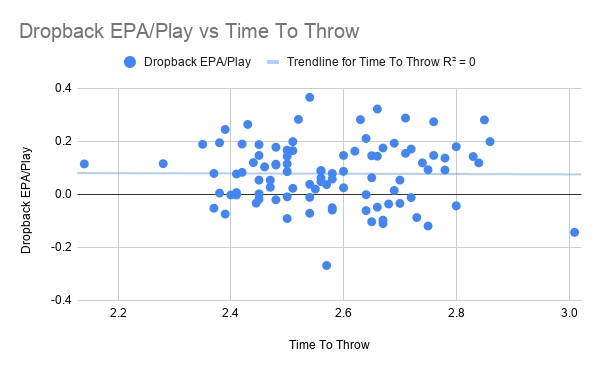

For starters, there is no evident negative effect between holding onto the ball longer and passing EPA/play:

If you get rid of the ball in less than 2.5 seconds, how are your receivers going to get down the field to create big plays? Look at the 2020 Steelers as a prime example of this. Yes, Ben Roethlisberger was able to get rid of the ball early and avoid sacks, but Pittsburgh also generated the least amount of explosive passes; recent Saints teams and the Washington Football Team this year fell into this trap as well. On the other end of the spectrum, Allen, Watson, and Russell Wilson all hold onto the ball for 3+ seconds, and are able to consistently produce plays down the field.

Wait, wouldn’t holding onto the ball longer lead to more sacks? Nope!

Quarterbacks who hold onto the ball longer do get pressured more often (r^2= .225), but since they are generally mobile and thus are more difficult to sack, they don’t necessarily get sacked more frequently. Thus, what good are the likes of Roethlisberger and Brees doing getting rid of the ball so quickly. At the end of the day, the trade-off does not make sense:

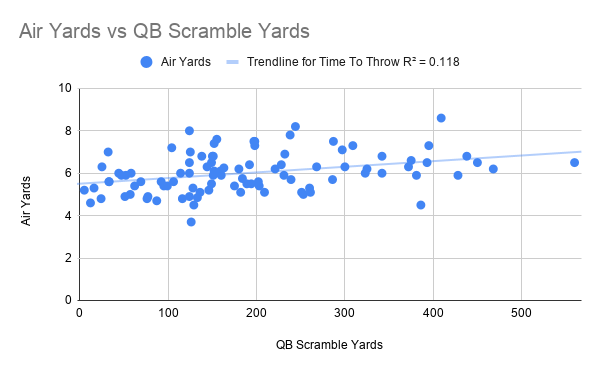

Quarterbacks who hold onto the ball longer give their receivers a chance to work down the field, and, thus, produce more air yards than those who get rid of the ball quickly. Since mobile quarterbacks hold onto the ball longer, it isn’t a surprise then that those who scramble more often produce more air yards as well. This definitely stems from a higher average depth of target (r^2= .305, .21), and, at the end of the day, makes them less replaceable. Brees and Roethlisberger got more than 50% of their yardage from the receivers after the catch, whereas Allen, Wilson, and Watson are responsible for a significant portion of their passing yards. The Saints and Steelers, meanwhile, shouldn’t struggle as much to replace their quarterbacks as the Bills, Seahawks, and Texans would, something we may see play out this offseason with Watson likely to request a trade.

When you are striving for a franchise quarterback, you ought to take shots on someone capable of high-end play. To this end, taking a quarterback who can scramble and holds onto the ball in hopes a big play, rather than one who is quick to take a check down, would appear optimal approach.

What Does This Mean For Offensive Lines?

In recent years, we have seen the wide receiver position cement itself as the second-most important. Based on a study I conducted in the offseason, pass protection held a minuscule effect on an offense compared to its quarterback and receiving corps. To add onto this, according to Josh Hermsmeyer of Five Thirty Eight, the correlation between pass-block win rate and passing efficiency isn’t particularly strong:

https://twitter.com/friscojosh/status/1353752340902252545

This, in my opinion, has a lot to do with what quarterbacks are capable of nowadays. With them holding onto the ball longer, alluding pressure more easily, and needing to produce big plays, the strength of the offensive line doesn’t matter as much- pressure will likely be invited regardless. We already know that one singular offensive lineman doesn’t move the needle, which is why teams in the upcoming draft should be wary of drafting Penei Sewell over the class’ quarterbacks and top receivers, but also maybe a sign that offensive lines as a whole are slightly hyper-focused on when looking at a quarterback’s supporting cast? After all, the Chiefs just made the Super Bowl without their starting offensive tackles, the Packers offense dominated the best defense in the league (Rams) without theirs, while the Bills, Bucs, and Titans maintained tremendous offensive efficiency without elite offensive lines. What all of those teams do have, however, is receivers who can create separation and create big plays. At the end of the day, star talent on the perimeter, as well as a quarterback capable of high-end plays, appears to win games.

Overview

So, what does this all mean? Is mobility a necessity?

Yes, it is better to have a mobile quarterback. The greater share a quarterback has on the team’s rushing yards, the more likely it is that they have an efficient rushing offenses. Meanwhile, mobile quarterbacks hold onto the ball longer, which in terms leads to them being able to produce more air yards by virtue of big plays down the field. Thus, they would appear to be far less replaceable than the typical “game manager”.

However, success is still tied to the passing game, and we’ve seen several zone-rushing attacks, primarily Kyle Shanahan disciples, be able to maintain some rushing efficiency. It would appear that scheme and the quarterback are the main two aspects of a rushing offense, and, at the end of the day, mobile quarterbacks need to be paired with a smart offensive play-caller, though that is true with all quarterbacks. Almost certainly, accuracy still remains likely the most important trait for a quarterback to have, so although the bar is higher for immobile quarterbacks to succeed, they certainly are capable of doing so. Tom Brady was Pro Football Focus’ second-highest graded passer and is going to the Super Bowl, after all; they just need to be able to make plays down the field.

Looking towards this offseason, this thinking will be important when analyzing the quarterback market. Matthew Stafford, for instance, is able to produce a large amount of air yards, which makes him an appealing fit for multiple teams, including the Colts. Furthermore, the Saints, Steelers (if Roethlisberger retires), and 49ers will be looking to replace quarterbacks whose play styles made them much more replaceable, while Deshaun Watson could be available to change the course of a team’s franchise. Looking towards the draft, Ohio State’s Justin Fields has been criticized for a high average time to throw, but as I’ve shown in this piece, that may actually be a positive. Thus, it comes as no surprise he has less of a share of his yardage come after the catch than any of the other prominent quarterbacks in this class. Additionally, Trey Lance, although a small school product, is likely worth a gamble based on his mobility and big-play ability.

Does this mean a pocket passer like Mac Jones cannot succeed? Certainly not. Jones is tremendously accurate and his deep-ball production is sound. However, he will have a lower margin of error, and is the type of bridge quarterback that will force teams to continue to look for the future. For teams in need of an immediate quarterback and could benefit from his cheap salary, such as the Broncos, 49ers, Colts, Steelers, and Saints, this could make him extremely appealing. For teams not ready to compete, however, he isn’t as logical of a fit.

Ultimately, we cannot afford to worry significantly about a quarterback’s propensity to commit negative plays, particularly early in their career, as long as there is enough positive play to match it. Personally, I would gladly take my chances with a volatile quarterback capable of high-end play over a safer “game manager” prototype, though, as always, one cannot afford to be rigid in the quarterback acquisition process. Moving forward, I am excited to see how quarterbacks continue to evolve, and most important, how offenses in general are built. Will it matter how strong an offensive line is? Will teams focus more on being 4-5 deep at the receiver position? How long until the replaceability of running backs catches on even more? Only time will tell!

One Comment Add yours